This has been a very big week for many educators and students as we return to school, either the physical or virtual classroom. Covid-19 has caused global disruption and education wasn’t immune from this. Obviously, the health and safety of our students is always the priority but teachers around the world have been working extremely hard to ensure learning and progress can still continue despite the challenges we faced.

Twitter is a fantastic online platform for sharing, learning and networking with other educators and on a global scale too. I have certainly learned a lot from the #EduTwitter community. Through Twitter I have been able to follow different teachers and leaders around the world. I am based in a wonderful British curriculum school in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates but I am originally from Wales so I am keen to keep up to date with developments and news linked to education in the UK. Through Twitter this week I have seen that lots of schools have had their back to school inset days or sessions ahead of the new academic year.

In 2019, my second book was published with John Catt that focused mainly on retrieval practice … hence the title – Retrieval Practice: Research and Resources for every classroom. I have been absolutely overwhelmed by the success it has achieved! It has been a #1 best seller on Amazon in various education categories and has hovered around the top three for 9 months alongside books by Tom Sherrington and Oliver Caviglioli (great company to be alongside). This week many teachers and senior leaders have contacted me via Twitter to tell me their inset sessions have centered on or discussed the research and ideas from my retrieval practice book. This is so lovely for me to know, that my book is having an impact and supporting schools, really is incredible. Aside from the fact I authored the book I am also delighted that schools are taking an evidence and research-informed approach to teaching and learning during professional development.

@87History using your research and ideas in our staff Teaching and Learning INSET today @TheOngarAcademy pic.twitter.com/zJT5ct6gTv

— Mrs RS (@ASST_HEAD) September 2, 2020

This focus on cognitive science is a very positive step in the right direction. Of course, professional development time needs to be dedicated to other areas such as safeguarding, pastoral provision and various aspects of teaching and learning such as literacy, feedback and other pieces of my teaching and learning puzzle I created, as shown below.

What is clear from Twitter and conversations with educators is that inset and training in some schools is still focused on things that many of us know to be well and truly debunked … the main culprit being learning styles (if you don’t believe me simply type ‘learning styles’ into the Twitter search bar to see a stream of recent tweets promoting this neuromyth). Whilst I do fully appreciate that context and variety are always key in education the concept of different styles of learning does not sit well with me. A lot of the reading and research I have encountered over the last five years has led me to the conclusion that there are in fact some ways that are deemed more effective when it comes to learning in comparison to others. The suggestion of no best way overall is a risky message to be delivered during inset.

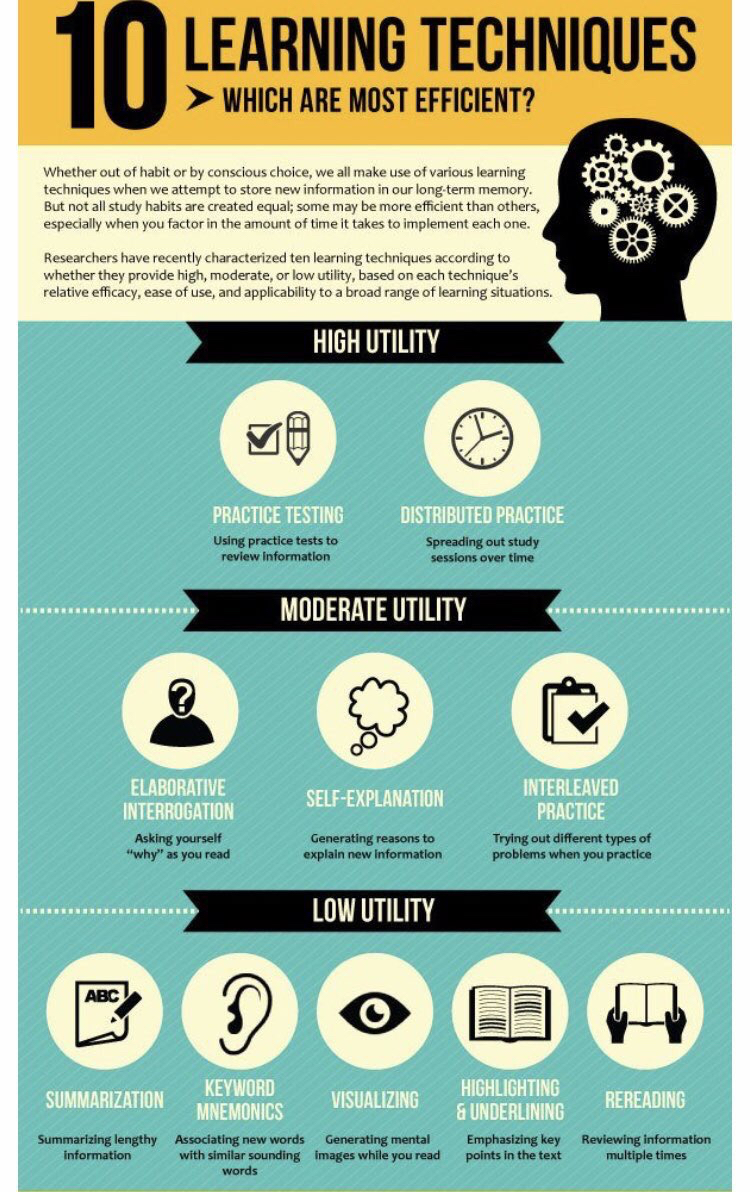

The work of Professor John Dunlosky et al has become quite well known and referenced in education. You can read more about this here, it is a great research summary that is clear and concise. This summary tells us that out of ten tried and test revision strategies some techniques were found to be more effective – such as retrieval and spaced practice – in comparison to other strategies that were deemed to be less effective, such as re-reading and highlighting. The key phrasing here is effective. Dunlosky makes the point that any student with a pen and paper can make progress, any revision strategy has to be better than no revision at all but some techniques are simply better, regardless of the individual.

Every individual is unique and this is wonderful, we embrace this as educators but when it comes to learning … we’re not as different as some might assume. Learning styles for many educators are a thing of the past to shudder at, with the notion of planning and creating different tasks to suit the visual, auditory or kinaesthetic learners in the classroom. The theory focuses on how students will have a preference to learn visually, via auditory information, through reading or writing, or kinaesthetically. These are the most well recognised learning styles, but Frank Coffield and colleagues identified 71 different theories of learning styles. Let’s take a moment to consider the huge workload implications of catering for 71 different learning styles …

Whilst, some might laugh and think this is very 2000’s it is still very much common practice which inset week this week has shown. I am aware of a school that received online training during lockdown with advice and guidance as to how they can support the different learning styles and preferences of their students during remote learning! The concept that teachers should strive to plan lessons and activities based on learning styles rather than what an overwhelming amount of research informs us to do, is a concern.

I do understand that the learning styles may be used to argue the case for variety in the classroom and I have shown through my writing and sharing online that retrieval practice is a strategy that can be adapted in a variety of ways both inside and outside of the classroom. Variety is different. In 2008 Cognitive scientist and accomplished author Daniel T Willingham posted a video on YouTube – Learning Styles Don’t Exist yet in 2014 that message clearly hadn’t reached a lot of educators. To show why this hashtag needs to be challenged is some research from 2014 (arguably as a profession we have moved on considerably in recent years but we haven’t completely moved away from this debunked theory) and this research does highlight the problem with learning styles in education.

In 2014 Professor Paul A. Howard-Jones asked over 900 teachers from different countries whether they agreed or disagreed (there was also an ‘I don’t know’ option) with the following statement: ‘Individuals learn better when they receive information in their preferred learning style (for example, visual, auditory or kinaesthetic).’ The percentages below show how many teachers of those asked, selected that they agree with the statement:

United Kingdom – 93%

Netherlands – 96%

Turkey – 97%

Greece – 96 %

China – 97 %

This demonstrates how influential learning styles have become across different countries around the world. The results highlight that many classroom teachers are familiar with learning styles, therefore, are likely to use this approach in their classroom if they believe individuals learn better as a result of doing so. Howard-Jones refers to learning styles as a ‘neuromyth’. Alan Crockard coined this term in the 1980s to refer to unscientific ideas about the brain in a medical capacity. This term was redefined in an OECD report (2002) as ‘a misconception generated by a misunderstanding, a misreading or misquoting of facts scientifically established to make a case for use of brain research in education and other contexts’. Why is this still being bandied around? When will learning styles disappear?

Willingham along with other well-known names in education such as Pedro DeBruyckere and Paul A. Kirschner have provided vast amounts of research and literature to dispel and challenge the learning styles theory for many years now. Ed Hirsch, author of the classic Why Knowledge Matters, building on the work of Willingham noted that ‘the evidence for individual learning styles is weak to non-existent’. Graham Nuthall, the author of one of my favourite educational books The Hidden Lives of Learners, also stated that there was no valid research evidence to support the claims that adapting classroom teaching to students’ learning styles makes any difference to their learning.

John Hattie’s well-known survey of 150 factors that affect students’ learning, highlighted that matching teaching to the learning styles of students was found to have an insignificant effect of little above zero. Authors of Make It Stick: The Science of Successful Learning discuss learning styles in their popular book, explaining that they found very few studies designed to be capable of testing the validity of learning styles theory in education. The studies that they did found that virtually none validate it and others even contradict it. I could go on listing the authors and academics that have discredited learning styles.

I think the main issue I have with the ideas, beliefs and implementation of learning styles is that the people that will suffer most from this approach are the students. Peps McCrea in Memorable Teaching wrote that learners are more similar than different in how they learn and teachers labelling of students in this way (learning styles) can be limiting … but I argue that it has the potential to be damaging to their progress and success, without even factoring the teacher workload elements.

The EEF have stated ‘there is very limited evidence for any consistent set of ‘learning styles’ that can be used reliably to identify genuine differences in the learning needs of young people and evidence suggests that it is unhelpful to assign learners to groups or categories on the basis of a supposed learning style’. It also adds that ‘labelling students as a particular kind of learner is likely to undermine their belief that they can succeed through effort and to provide an excuse for failure’. Again, another motivation for challenging and debunking myths and taking an evidence-informed approach to education.

Below is the abstract from an article written by Paul A. Kirschner (2017) entitled ‘Stop propagating the learning styles myth’ which is an excellent summary of why the nail needs to be firmly planted in the learning styles coffin once and for all!

“We all differ from each other in a multitude of ways and as such we also prefer many different things whether it is music, food or learning. Because of this, many students, parents, teachers, administrators and even researchers feel that it is intuitively correct to say that since different people prefer to learn visually, auditively, kinaesthetically or whatever other way one can think of, we should also tailor teaching, learning situations and learning materials to those preferences. Is this a problem? The answer is a resounding: Yes! Broadly speaking, there are a number of major problems with the notion of learning styles. First, there is quite a difference between the way that someone prefers to learn and that which actually leads to effective and efficient learning. Second, a preference for how one studies is not a learning style. Most so-called learning styles are based on types; they classify people into distinct groups. The assumption that people cluster into distinct groups, however, receives very little support from objective studies.

Finally, nearly all studies that report evidence for learning styles fail to satisfy just about all of the key criteria for scientific validity. This article delivers an evidence-informed plea to teachers, administrators and researchers to stop propagating the learning styles myth.”

We are now fortunate as a profession to be moving in a very positive and hopeful direction. The #ResearchEd community and events are doing a great job to promote an evidence-informed approach to education as well as the authors, bloggers, teachers, leaders and cognitive scientists all collaborating together. There are some well-known strategies that are regarded and described as “better” than others so surely learning is far too precious and important to go against and ignore the vast amounts of research available to us? All educators simply want the best for their students in their classroom but despite best intentions, we need to reflect on how we approach and promote learning strategies with our students.

We are moving in the right direction but we are not there yet.